Get tough: A lenient capital gains tax regime has been distorting incentives

T. C. A. Anant | 15 Aug 2024

Summary

- Not only have capital gains had an indexation benefit that lets the inflation effect be sliced off, it overstated the price-rise experience of India’s well-off investor classes. Privileging a single income category warps incentives and diverts money towards privileged earning sources. Let’s fix it.

The recent budget presented by the finance minister saw a spurt of adverse commentary on the proposals relating to capital gains transactions, particularly with reference to the removal of indexation benefits.

In response, the government partially restored the benefits to a segment of taxpayers. However, as the FM has promised re-visiting and simplifying the entire structure of direct taxes, it is worth taking a closer look at these issues.

Indexation in capital gains was first introduced in the 1992-93 Budget, when the FM then had stated, “The present tax treatment of long-term capital gains has been criticized on the grounds that the deduction allowed in computing capital gains is not related to the period of time for which the asset has been held. It does not take into account the inflation that may have occurred over time. The Chelliah Committee has suggested a system of indexation to take care of the problem, and I propose to accept its recommendation.”

Based on this, the Income Tax Department started producing a cost inflation index which has been used to compute long-term capital gains (LTCG). The only substantial change which occurred was in 2017, when the base year for calculating this index was changed from 1981 to 2001.

As per the Finance Bill of 1992, “‘Cost Inflation Index’ for any year means such Index as the Central Government may, having regard to seventy-five per cent of average rise in the Consumer Price Index for urban non-manual employees for that year, by notification in the Official Gazette, specify in this behalf.”

The Central Statistical Office (CSO) used to produce the consumer price index (CPI) for urban non-manual employees till 2010, after which it was replaced by CPI Urban.

Another factor that must be kept in mind is that in 2004, the budget removed the taxation of LTCG on equity, and instead introduced the securities transactions tax. In 2018, LTCG taxation on equity was reintroduced, but without indexation benefits. Thus, the recent removal of indexation was primarily focused on capital gains arising from non-equity assets.

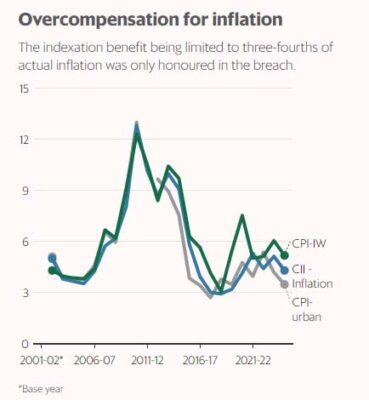

The accompanying graph shows the cost inflation index in comparison with both CPI-IW and CPI-Urban (the series of CPI-Urban actually contains CPI-Urban Non-Manual Employees till 2010, after which CPI Urban was produced by the CSO). It is clear from the graph that from 2001 onwards, the principle of having the inflation index capture only 75% of the average rise in CPI inflation was (in the words of Shakespeare) a practice “more honour’d in the breach than the observance.” In this context, note that the Chelliah Committee had observed, “The logic of limiting indexation to 75% of the CPI is that the tax schedule applicable to other incomes will not be automatically indexed to inflation.” Thus, capital gains were additionally privileged over all other sources of income.

The accompanying graph shows the cost inflation index in comparison with both CPI-IW and CPI-Urban (the series of CPI-Urban actually contains CPI-Urban Non-Manual Employees till 2010, after which CPI Urban was produced by the CSO). It is clear from the graph that from 2001 onwards, the principle of having the inflation index capture only 75% of the average rise in CPI inflation was (in the words of Shakespeare) a practice “more honour’d in the breach than the observance.” In this context, note that the Chelliah Committee had observed, “The logic of limiting indexation to 75% of the CPI is that the tax schedule applicable to other incomes will not be automatically indexed to inflation.” Thus, capital gains were additionally privileged over all other sources of income.

This is particularly egregious when we note that only 5% of returns filed had any LTCG to report in 2022-23 (a similar proportion reported short-term capital gains).

Though the statistics do not disaggregate capital gains from various sources, it is likely that the bulk of these are on account of gains from equity transactions. Thus, policy is being influenced by a tiny community of relatively high income tax payers.

The issue of high income is important because the inflation index already overstates the inflation experience of high income households. This is because CPI Urban has a 36.3% share for expenditure on food and beverages (based on the 2011-12 National Sample Survey). As I show in another article, this would now be 34% as per the 2022-23 Household Consumption Expenditure Survey.

Using this data, it is possible to further compute the inflation experience of different consumption fractiles, and doing so shows that the share of expenditure on food and beverages for the top 10% of expenditure classes would actually be as low as 27-29% of their outgo. It is this top 10% who are likely to be the ones generating the bulk of non-equity capital gains in the first place.

Highlighting the changing share of food expenditure is important because a significant part of India’s headline inflation measure is on account of food inflation. Since the impact of food inflation on this class is relatively small, investors have been given yet another source of privilege.

Much of the argument on social media has been that the gain in asset prices is small and therefore the removal of indexation benefits is an unjust imposition. This seems particularly duplicitous because indexation should have been related to inflation experienced by investing classes, rather than riding on the higher inflation experience of much poorer sections of society.

Inflation affects all classes of taxpayers with various sources of income. This is on account of both ‘bracket creep’ (as inflation leads to a rise in nominal income and puts taxpayers in higher tax slabs) and non-indexation of the deductions available. Privileging one category of income leads to the distortion of incentives and diversion of resources towards privileged earning sources. An ideal direct tax system would eliminate such distortions.

Further, taxpayers in general come from higher-expenditure classes in our society. Any index reflecting average behaviour overstates their inflation experience. Thus, any form of inflation indexing should ideally be based on their inflation experience (and less than that of the average).

It is important to note that the principles enunciated in the Chelliah Committee report on tax reform continue to be valid, and should be revisited keeping in mind the need for equitable treatment of different income sources. An opportunity for this exists because of the FM’s commitment to revisit and simplify the overall direct tax experience.