India’s inflation aim: Let us go by its reality and not the perception

There is sufficient evidence to show that perceived inflation is higher and we must not be misled into making policy errors

T C A Anant | August 22, 2024

Recently, writing in the Economic Survey, the chief economic advisor observed that it is worth exploring whether India’s inflation targeting regime should focus on non-food inflation. The reasoning was that monetary policy is more effective in counteracting price pressures that arise out of excess aggregate demand, whereas food inflation is usually on account of supply constraints.

In contrast, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) governor recently spoke after the monetary policy meeting and observed that food inflation is a major factor in determining inflationary expectations and therefore continues to be a matter of concern. He pointed out that “the public at large understands inflation more in terms of food inflation than the other components of headline inflation. Therefore, we cannot and should not become complacent merely because core inflation has fallen considerably.”

In view of these observations, it is worth revisiting an old column of mine in this paper—“It might be time for India to reconsider its indicator for inflation targeting” (15 November 2023). The article points out that inflation is not a singular phenomenon. There are in fact many different inflations, which are not necessarily highly linked. Monetary policy has different consequences for these different inflations.

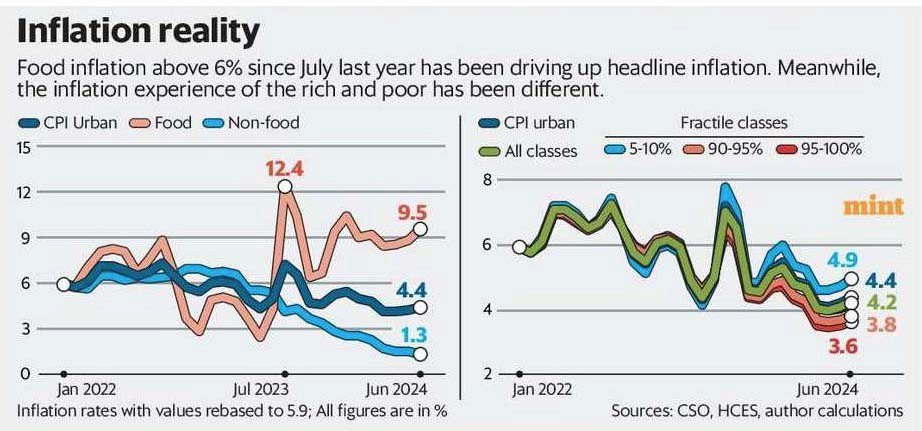

To understand the implications of this, it may be useful to see the trajectory of recent inflationary behaviour, which is depicted in the accompanying chart. We see that food inflation in urban areas spiked in July 2023 and has since stayed above 6%. A similar pattern is seen in rural areas as well. In contrast, inflation in non-food items has been steadily declining and is well below 2% at present.

A consequence of the persistently high food inflation is that headline inflation, as measured by the consumer price index (CPI) series using a weighting basket from 2011-12, has remained above the 4% level. This aggregate headline inflation to which the governor assigned considerable importance in influencing inflationary expectations has major problems.

First, as the recent Household Consumption Expenditure Survey (HCES) revealed, the share of food expenditure in the overall consumption basket has declined since 2011-12. In urban areas, average expenditure on food has declined from 36.4% to 34%. In rural areas the decline has been even sharper—from 54.2% to 45.7%. It needs to be understood that the weighting diagram for the CPI is derived from the expenditure patterns of the average household. These changes in the share of food consumption would themselves imply that ‘real’ (as against published) inflation is lower, and would be below 4% in recent months.

Further, the HCES data gives us consumption patterns by fractile classes of households. Examining these, we can see that the share of food in total expenditure in the poorest 5% of urban households is 44%, while the share of food in total expenditure in the richest 5% is 27%. If we were to recompute urban CPI for these different expenditure classes, we would observe that there is a significant divergence in the experienced headline inflation of the poorest segment as compared to the richest segment (depicted in Chart 2).

When the governor talks about inflationary expectations, it is important to put this in context. A column by Deepa Vasudevan in this paper last year (‘How useful are RBI’s inflation surveys?’, 5 June 2023) brings out an interesting facet of a household’s perceived inflation rate, which is almost always significantly above the actual inflation rate, and is mostly influenced by short-term changes in prices of essential, frequently purchased goods such as food or fuel. If a misperception of households anchors policy, then it has serious consequences for the economy.

While monetary policy does not have a direct influence on agricultural supply, it does play a very important role in determining the costs faced by domestic manufacturers.

A restrictive policy raises the cost to domestic manufacturing, which has numerous negative consequences for the economy. Domestic manufacturers lose competitiveness to their global counterparts, leading to both adverse pressure on the balance of trade, as well as a slowdown in domestic employment. If the government were to respond to the deterioration in balance of trade by increasing tariff barriers, it would lead to a rise in domestic prices, and slowdown in overall growth.

The RBI governor has a point that persistently high headline inflation can become self-sustaining in an environment where the government is fiscally imprudent, as was seen in India in the immediate aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis or more recently in the US in the aftermath of covid. In contrast, when a government is following a prudent fiscal strategy, rigid adherence by RBI to an outdated headline inflation measure could derail the process of economic recovery. In light of these observations, there are some important considerations that the Monetary Policy Committee must keep in mind.

First, since HCES data is available, a re-weighting of existing CPI item indices can be done within RBI itself to give a better indicator of headline inflation. Second, as the old literature on instruments and targets brought out, our target itself must be directly related to the action of the instrument. Thus, seeking to control supply side inflation of food through monetary instruments could well be counter-productive. It is in this context that the chief economic advisor’s observation that there is a need to revisit the framing of the inflation targeting mandate needs to be seen. It would be better to align inflation targets with the reality instead of perceptions, which are being manipulated by a somewhat opaque social media dialogue.